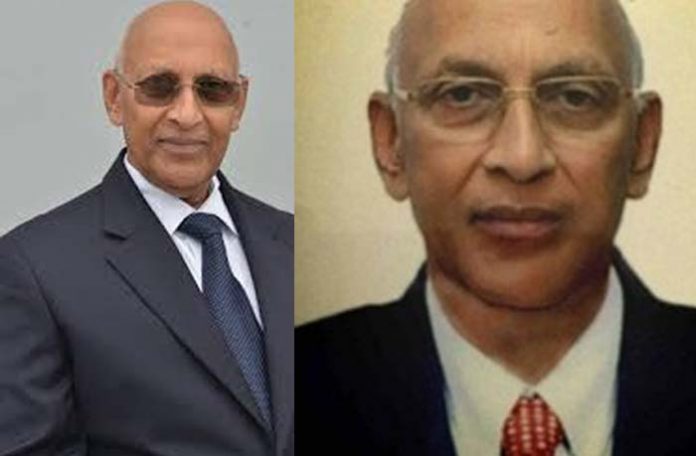

Random reflections on the current state of media by a consumer of journalism and a member of the legal community, Justice Goda Raghuram, Director, National Judicial Academy, India.

It is, in fact, an excellent treatise on the present-day world journalism. Justice Goda Raghuram has referred to many famous journalists and authors, quoting copiously, to drive home his point. It is eminently readable and a must read for those who are engaged in journalism, judiciary, politics and public administration. All of us who are interested in thriving democracy have to read this article with undivided attention. It has a lot of relevance today when Republic TV’s Editor-in-Chief Arnab Goswami, being in jail, made Indian journalism a hot topic of discussion and insightful discourse. If you want to know why titillation, disaster, violence, crime, negativity and tragedy occupy the centre-stage in the content of the media today, read this till the last word.

-Editor.

We are at an interesting and challenging bend of history. There is a deep deficit of faith and credibility in the formal institutions of governance. Reform of our public institutions and return to professional behavior, democratic responsibility and to rational conduct by our State actors would depend on citizens holding institutions and incumbents accountable. This is achieved only by knowledge and continuous and detailed information. This is where the media comes in.

Informed citizenry

Maintaining peace and equanimity of the social order; nurturing equitable development and progress in our large, complex and deeply plural society; making our public institutions effective and accountable; reforming our malfunctioning public services; disciplining delinquent public actors; and curbing arrogant propensities of our public representatives, requires an adequately informed citizenry.

Since the dawn of cognitive human existence, the homo sapient has been driven by the need for accurate and reliable information that helps sustain existence in a challenging natural and societal habitat.

Competent, responsible media

Today, a professional, competent and neutral media, sensitised to the awesome, onerous and continuous responsibility of informing democratic society of its obligations and rights; of its essential sovereignty and of the unvarnished anatomy of their public institutions, is a non-derogable and vital tool. A competent and responsible media is perhaps the only remnant factor that validates the optimism, of a sustainable future.

Judge Learned Hand expressed the critical role of the media when he observed: The hand that rules the press, the radio, and the far-spread magazine, rules the country (extracted from Gary A. Hengstler –The Media’s role in changing the face of U.S. Courts, http://usinfo.state.gov/journals/itdhr/0503/ijde/hengstler.htm)

What constitutes news?

Throughout history, world-over and across cultures, from the most isolated, culturally static tribal societies to the most advanced, informed and dynamic, people share essentially the same definition of what constitutes news; people share the same kind of gossip and look for the same quality in the messenger they choose to gather and deliver news.

Since the dawn of our cognitive existence and throughout our psycho-social evolutionary process, news constituted the essential component of societal existence. News is essential to live our lives, to associate with each other, to form communities – tribal, national or multi-national, to protect ourselves, to identify friends and foes, to preserve our liberties and to have control over the systems and institutions of governance in modern societies; irrespective of the architecture of governance – whether a tribal chief, a king, a dictator; or a democracy, whether federal or unitary.

Integrity of news critical

Journalism is the medium and the system societies generate to supply news. Therefore, the character and integrity of the news and the institutions of journalism are of critical concern. Journalism influences the quality of our lives, moulds our thoughts and indexes our culture. It provides a unique component to our culture – independent, reliable, accurate and comprehensive information that we as citizens require, to be free.

In a scintillating analyses of the criticality of free speech for democratic society Mathew. J (in his dissenting opinion in Bennet Coleman and Co. Ltd. vs. Union of India & Others – A.I.R. 1973. S.C. 106) observed:

“The crucial point is not that freedom of expression is politically useful but that it is indispensable to the operation of a democratic system. In a democracy the basic premise is that the people are both the governors and the governed. In order that the governed may form intelligent and wise judgment it is necessary that they must be appraised of all the aspects of a question on which a decision has to be taken so that they might arrive at the truth.

Journalism subverts democratic culture

Journalism that is ordered to be or which provides something other than the above characteristics subverts democratic culture. History verifies this reality. From the Sumerian, Greek, Egyptian, or Roman empires; through Nazi Germany, the former Soviet Union, the Middle-eastern monarchies, dictatorships – old and new; and fundamentalist States, reinforce the fact that distorted journalistic (or even proto-journalistic) values, whether the distortion be on account of external control or internal pathology, subvert cultures, enfeeble the population, promote inequality, and sooner than later, contribute to the fall and decline of society.

In places like Singapore news is controlled to encourage capitalism and discourage participation in public life. To an extent initially; and increasingly over the past few decades, in India too, corporatized Media is seen to prioritize ownership interests to individual liberties, to sustainable development or to the living index of the most disadvantaged, under-privileged and the relatively oppressed sections of our population.

Media pathology

Corporatized (and mutant variants, the denominational, parochial and/or insular interests promoting species) Media and its associated pathology started in the United States in a more purely commercial form. News outlets owned by large corporations are employed to promote their conglomerate parent’s products, to engage in subtle lobbying or corporate rivalry; or are intermingled with crass advertising to boost profits. This pathology becomes exponentially malignant when the corporatized Media house or group owes loyalty to a broad political or class formulation. When this happens, political discourse in the society which is the life-blood of a democracy becomes garbled, incoherent, slanted and wholly distorted.

The fundamental assumption as to the vital importance of the media to democracy is seriously compromised by concentration of power and control of media in a few and insular hands. As Zachariah Chafee, Jr observes:Instead of several views and facts and several conflicting opinions, newspaper readers in many cities, or, still worse, in wide regions, may get only a single set of facts and a single body of opinion, all emanating from one or two owners.

Mathew. J (in Bennet Coleman, supra) refers to the analyses of Jerome A. Barron to conclude: “Our constitution has been singularly indifferent to the reality and implications of non-governmental obstructions to the spread of political truth. This indifference becomes critical when a comparatively few private hands are in a position to determine not only the content of information but its very availability.

Fourth estate of democracy

Media is called the fourth estate of democracy. This is because of the power it wields and the oversight function it exercises. The other three great estates – the Legislature, Executive and Judiciary are structurally and textually accountable to the public and there are entrenched rules that define and execute this accountability, however nebulous in operative reality!

The Fourth Estate is equally vital and its effective functioning is of critical concern to the survival of democracy. In this sense the Fourth Estate must be and is accountable.

What are the norms that define this accountability and how the accountability is to be enforced should the need arise, are deeply problematic and contestable areas. But this much is indisputable. Media which exercises enormous influence to shape the contours of democracy exercises its role in the name of the people. It should work for the people and is liable to be controlled by the people. At an empirical level what is at stake in defining the public accountability of media is the issue whether as citizens we have access to independent, reliable information that makes it possible for us to effectively govern ourselves.

The Italian-born English poet Humbert Wolfe described the Press of his day in the following terms:

You cannot hope to bribe or twist, thank God! the British journalist. But, seeing what the man will do unbribed, there’s no occasion to.

Irresponsible, insensitive

There is a respected body of concerned citizens in India who believe that the mass media have become monstrous, self-righteous, bereft of self-criticism, sensationalist and scandal-obsessed, often irresponsible and generally insensitive. These general tendencies have also been commented upon occasionally. There was widespread public condemnation of the essentially insensitive and even down-right dangerous handling of the terrorist attacks in Mumbai in November, 2008, by some sections of the media. There are even responsible sections of the media who lament the tendency to sensationalism; obsession with irrelevance; and with Television Rating Points (TRP’s) at the expense of honest reportage of events and issues that matter to most of the people. We are witness to shocking exposes of the growing phenomenon of paid news, an element which ridicules any pretence of objective and honest reporting. Nevertheless, the explicit desire to sensationalise and the equallystrong desire to present news in ways that suit corporate bosses of media conglomerates have come to define the way most mass media in the country operate to-day. This part of my observation is the distillate from an article in the respected journal –The Frontline. Where the ownership and control of the media or a section of it is captured by a sectional, denominational or insular interest, paid news transmutes into the genetic component of such entity; a house journal masquerading as a news media.

Public distrust in journalists

In 1997 a group of highly respected media persons including editors of several major newspapers in the United States, top journalism educators and some of the most prominent authors in the US gathered at the Harvard Faculty Club (HFC), since they were concerned that something was seriously wrong with the profession of journalism. They felt that much of the work of their colleagues in the profession was damaging instead of serving the larger public interest; that increasingly the public distrusted journalists and even hated them; that increasingly Americans were thinking that the Press did not care about the people, did not perform the watchdog role and did not protect democracy. Many of the gathered veterans at the HFC were disturbingly in agreement with the public perception. They therefore set about to examine the origins, the history, the core purposes of the profession; the fundamentals behind journalism’s evolutionary success and tried to identify the basic and ethical values that would sustain the profession. This meeting of the HFC evolved certain core and clear principles as to the essential role of journalism.

Nine essentials of journalism

The HFC conclave identified the essential purpose of journalism to be: to provide people with the information they need to be free and self-governing. The nine elements identified as the essentials of journalism are:

- Journalism’s first obligation is to the truth;

- Its first loyalty is to citizens;

- Its essence is the discipline of verification;

- Its practitioners must maintain an independence from those they cover;

- It must serve as an independent monitor of power;

- It must provide a forum for public criticism and compromise;

- It must strive to make the significant interesting and relevant;

- It must keep the news comprehensive and proportional; and

- Its practitioners must be allowed to exercise their personal conscience.

I will come back to the nine elements of journalism a bit later. Reverting to the topic of accountability; media accountability is sometimes confused with self-regulation. It does include self-regulation but is a far wider concept. Self-regulation implies that media impose rules upon themselves. Most often media owners initiate in-house discipline for fear that a government will legislate restrictions to their freedom of enterprise, taking public hostility towards media as a pretext. Sometimes journalists initiate rules to ensure good service and to protect their profession.

Accountability means being accountable. Accountable to whom is the question. Clearly and obviously, the accountability is to the public. While regulation involves control by the government of the day and self-regulation involves only the media industry, media accountability involves Press including the electronic media, the profession and the public. Somewhere in the middle of the 20th century the Press Council evolved involving these three groups in order to mediate complaints by users against the media. Most western European nations; and in Eastern Europe, Africa and Asia as well, the Press Council has come into its own. There are several structural, organisational and compositional varieties in the architecture and operation of Press Councils, in different countries and societies.

Operational deficit with Press Councils

The operational deficit with many Press Councils across the globe is that they tend to consider themselves as complaint councils and insist on mediating and not on adjudicating against the media, if they can avoid it. On a holistic perspective, the role of the Council is not just to satisfy a few individuals or groups who have been heard by the media; not just to avoid law suits; and not just to discourage the State or limiting the freedom of the media to make money. A Press Council is meant to improve the news media. Many Press Councils keep a low profile.

A vibrant Council on the other hand should not avoid seeking publicity, taking positions, establishing case law and taking initiatives even when no complaint is lodged. It should also assume functions like reporting on the state and evolution of the media and periodic audit of the media in terms of its essential functions. A Press Council should take interest in the training of journalists to improve professionalism and take up research on how the media actually functions, what influence it exercises and what citizens need from them.

Press Council should monitor media accoutability

The Press Council should also encourage evolution of other Media Accountability systems. Other Media Accountability systems could be classified into:

- Documents;

- People; and

- Processes.

Each of these categories in accounting systems has several aspects. I mention but a few. Among the accounting systems falling within the category of documents are:

- a hand-book of ethics, listing rules which media professionals have discussed and/or have agreed upon, preferably with input by the public. These should be put in the public domain;

- an accuracy and fairness questionnaire, mailed to persons mentioned in the news or published for any reader to fill out;

- a website offering journalists information and advice on promoting accountability and teaching the public how to evaluate the media; and

- an year-book on journalism criticism, written by reporters and media users and edited by independent academics.

People as individuals or groups constitute the second tier of accountability. This may consist of:

- an in-house critique or a contents evaluation commission, to monitor the newspaper or channel for breaches of the code, with or without making their findings public;

- an in-house ethics regulator operating in the news room, to raise reporters’ or editors’ ethical awareness; to encourage debate; and advise on specific problems;

- media reporters, highly trained, professional and neutral to monitor the media and give the public full and unprejudiced reports;

- a whistle-blower with entrenched and assured independence who could bring to light abuses within the media company;

- a consumer reporter to sensitise readers/viewers against misleading advertising and who intervenes on their behalf;

- a complaints bureau or a customer service unit to entertain grievances and requests;

- a disciplinary committee set up by a union or other professional association to ensure that its code is respected, under pain of expulsion; and

- media observatories set up by journalists to monitor attacks on Press freedom, adherence to the code, to receive complaints and to debate ethical issues with publishers.

Another level of media accountability system involves processes. These include:

- requirements of a higher education standard to qualify as a journalist and qualification in mass communications at higher levels;

- a separate curriculum of media ethics, made compulsory for all students of journalism;

- further and continuing education for working journalists; including workshops, seminars and occasional long duration fellowships at Universities;

- building data-base of errors and pathologies in the functioning of the media, so as to identify patterns and take corrective measures;

- a system of external ethical audit where independent external experts evaluate the ethical awareness, guidelines and conduct within the newspaper or channel;

- periodical survey – locality or nation-wide, to obtain accurate feed-back on public attitudes towards all or some components of the media; and

- International co-operation to promote media quality and accountability.

Before proceeding to outline the elements of journalism, I had adverted to earlier, it is necessary to briefly refer to the complex and multi-dimensional linkages among the media, good governance, democracy and sustainable and peaceful development. Media shapes public opinion but is in turn influenced and often manipulated by different interest groups in the society. Media can promote democracy by educating voters, protecting human rights, promoting tolerance and accommodation amongst social groups and ensuring that governments are transparent and accountable. Media can play anti-democratic roles as well. They can inject or promote fear, division and violence and thus instead of promoting democracy, can contribute to democratic decay.

A fearless and effective watchdog is critical in fledgling democracies where institutions are weak, homo-centric and persuaded by political pressure. When legislators, judiciaries and other oversight bodies are powerless against the mighty or are themselves corruptible, media is often the only check against abuse of power. To efficiently deliver upon this role, media must play a heroic role, exposing the deficiencies, the excesses or the delinquencies of legislators, bureaucrats or magistrates, despite the risks. A watchdog Press is the guardian of public interest, warning citizens against those who are doing them harm. Thomas Jefferson famously declared: Were it left to me to decide whether we should have a Government without newspapers or newspapers without Government, I should not hesitate to prefer the latter.

Amartya Sen, the Nobel Laureate, ascribed to the Press’ cleansing powers and outlined the need for transparency guarantees such as a free Press and flow of information. Sen argues that information and critical public discussion are an inescapable and important requirement of good public and the Media have a clear instrumental role in preventing corruption, financial irresponsibility and under-hand dealings.

The nature of media ownership is a very serious problematic for the effective functioning of the media and is critical to its essential role as an independent monitor of power. In many countries ownership of the media is controlled by a few vested and political interests. A study of 97 countries by the World Bank in 2001 for incorporation in the World Development Report discussed that throughout the world media monopolies dominate. This report analysed that only 4% of media enterprises are widely held; the majority have ownership structures dominated by business or political interests; family controlled newspapers account for 57% of the sample and families control 34% of television stations. The study concluded that the media industry is owned overwhelmingly by parties most likely to extract private benefits of control. The result is garbled, distorted or prejudicial information served as news and editorial content. There is also a selective acquiescence, muted criticism and a general hushing of public debate on crucial issues.

In his Bennet Coleman dissent Mathew. J pointed out: With the concentration of mass media in a few hands, the change of an idea antagonistic to the idea of the proprietors of big newspapers getting access to the market has become very remote. It is no use having a right to express your idea, unless you have got a medium for expressing it. The concept of a free market for ideas presupposes that every type of ideas will get into the market and if free access to the market is denied for any ideas, to that extent, the process of competition becomes limited and the chance of all the ideas coming to the market is removed.

After stating that economic power is exercised also through control over mass media of communication, the Mahalanobis Committee stated: “Of these, newpapers are the most important and constitute a powerful ancillar to sectoral and group interests. It is not, therefore, a matter for surprise that there is so much inter-linking between newspapers and big business in this country, with newspapers controlled to a substantial extent by selected industrial houses directly through ownership as well as indirectly through membership of their board of directors. In addition, of course, there is the indirect control exercised through expenditure on advertisement which has been growing apace during the Plan periods. In a study of concentration of economic power in India, one must take into account this link between industry and newspapers which exists in our country to a much larger extent than is found in any of the other countries in the world (emphasis supplied).

Media promotes democracy, good governance

There are many good practices whereby the media promotes democracy and good governance by pursuing neutral, professional and integrity-based investigative reporting. The media serves as a watchdog and investigative reporting on corruption, human rights violations and other forms of wrongdoing help build a culture of accountability in government and strengthen democracies. Serious investigative reporting must however not be confused with flippancy, disproportionate sensationalism or disguised blackmail. Nor is it a one-time affair. The investigation must be clear, penetrating, continuous; and be pursued to the logical conclusion of ferreting out the facts of the wrongdoing. Investigative journalism to be effective and credible requires skill apart from ethical values and these are obtained only by special training on reporting techniques; on reading financial statements; constructing data-bases; and researching on the internet or by cultivating human intelligence, i.e., by personal contacts with the concerned.

Another vital role the media performs is as an information tool and a forum for discussion. In democratic societies where elections are the key to democratic exercises and in societies where caste, language, religion or other such narrow constraints diminish the bases of democracy, Media plays an important role in highlighting the positive and negative characteristics of political parties and candidates; including past performance, personality, record of service and the track of integrity. In societies where corruption is a serious factor, the media must highlight the difference in wealth and assets of the candidate pre and post public office. Views, ideologies, theories of governance, a critical analyses of election manifestos; whether particular or specific promises that are made in the manifestos are sustainable given the economic and differential developmental reality, are areas where the media serves as a vital tool for information dissemination and could provide a forum for discussion and enlightenment of citizens. This, in turn, deepens democracy and vitalises governance.

Peace, consensus builder

Media also serves as a peace and consensus builder in insular societies. The role of the media is significant in moderating passion, mediating between warring sections and providing a voice of sanity. On this role of the media there is serious criticism about the Indian experience. Serious analysts point out that media has generally not played a neutral role in conflict situations. In many cases they have fanned flames of discord by taking sides, muddling the facts, peddling half-truths or reinforcing prejudices. Too often, sections of the media have been criticized for sensationalising violence without explaining the roots of conflict.

Many non-governmental organisations across the world are now endeavouring to train journalists in “peace journalism” which is intended to promote reconciliation through careful reportage that lends voice to all sides of a conflict and resists explanations for violence. Different levels of media can play a constructive and hierarchical role in mediating conflict and brokering peace. These differ in context on whether the media entity is a national, regional, State or local provider.

Journalism is so fundamental to human liberty and to democratic societies that societies that want to suppress the freedom must first suppress the Press, since journalism interlocks people.

This primary purpose of journalism is however being undermined today and is challenged in ways not seen earlier in human history, at least in liberal societies. Technology is shaping a new economic organisation of information companies which is subsuming journalism inside it. Today the threat is no longer or even primarily from government censorship. The new danger is in independent journalism being dissolved in the solvent of commercial, partisan or sectarian interests’ leveraged communication and synergistic self-promotion.

Constitutional guarantee threatened

The Indian Constitution’s implied guarantee of a free Press as an independent institution is threatened for the first time in our history even without government meddling.

There are many in the profession including many who are well-meaning who argue that to define journalism is to limit it. That is why journalists avoid professional licensing like doctors and lawyers. These concerned voices also argue that defining journalism will only make it resistant to change with the times. In reality, the resistance to definition in journalism is not a core and vital principle but a fairly recent and largely commercial impulse. Publishers a century ago routinely championed their news values in front-page editorials, opinion pages and company slogans, and just as often publicly assailed the journalistic values of their rivals. This was marketing. Citizens chose which publications to read based on their style and their approach to news.

It was only as the media began to assume a more corporate and monopolistic form that it became more reticent. History has it that lawyers advised news companies against codifying their principles in writing for fear that they would be used against them, somewhat like our Parliamentary privileges. Avoiding definition was thus a commercial strategy.

The central purpose of journalism is to tell the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth – so that people will have the information they need to be sovereign. Journalism has also a broader social and moral obligation, as Pope John Paul, the 2nd, observed1: With its vast and direct influence on public opinion, journalism cannot be guided only by economic forces, profit and special interest. It must instead be felt as a mission in a certain sense sacred, carried out in the knowledge that the powerful means of communication have been entrusted to you for the good of all.

Another function of news is to cater to the awareness instinct in humans. People crave news out of a basic instinct; they need to know what is going on the next door; to be aware of events beyond their direct experience. Knowledge of the unknown provides security, allows them to plan and negotiate their lives; and exchanging this information becomes the basis for creating a community and making human connections for the common good of all and therefore of coalescing societies.

Democracy fundamentally flawed

Walter Lippmann, among the world’s most famous journalists, an American, observed in a best–selling and authoritative work analysing journalism, Public Opinion, that democracy was fundamentally flawed. People, he said, mostly know the world only indirectly, through the pictures they make up in their heads. And they receive these mental pictures largely through the media. The problem, Lippmann argued, is that: the pictures people have in their heads are hopelessly distorted and incomplete, marred by the irredeemable weaknesses of the press. Just as bad, the public’s ability to comprehend the truth even if it happened to come across it was undermined by human bias, stereotype, inattentiveness, and ignorance. Lippmann’s momentous work in the 1920’s, Public Opinion, gave birth to the modern study of communication.

The discipline of verification is not a mere micro element of journalism. It has a macro dimension which is more vital and this element is subverted in a large measure by a commercialised culture of journalism and corporatization of the media. The malady becomes malignant, epidemic and rampaging when there is an adulterous relationship with commerce and politics as well.

Ralf Dahrendorf, a former Director of the London School of Economics, in a scintillating essay –After 1989: Morals, Revolution and Civil Society2, makes a perceptive observation of a media baron denigrating the benefits of democracy. Dahrendorf quotes media baron, Rupert Murdoch’s comment when his company won the television rights in Singapore. Murdoch had said:

Singapore is not liberal, but it is clean and free of drug addicts. Not so long ago it was an impoverished, exploited colony with famines, diseases and other problems. Now people find themselves in three-room apartment with jobs and clean streets. Material incentives create business and a free market economy. If politicians tried the other way around with democracy, the Russian model is the result. 90% of the Chinese are interested more in a better material life than in a right to vote. World-over not only in the democratic context but in several other contexts as well there is a growing list of other examples; of ownership, subordinating journalism to other commercial interests.

Another major pathology of much of journalism today is corporatization transiting through conglomeration and indexed by globalisation. News chains and corporate media houses that own outlets across different communities are throwing up newer and exponentially accelerating challenges for the ethics of journalism. First Hollywood and now Bollywood, Tollywood and other woods manufacture/make more action movies and the reason is the commercial element. Action sequences enhanced by technology and graphics have no language barriers and require no translation and make more money in foreign or other language sales.

News decisions by conglomerated media houses are based on a similar set of simplified cultural cues. This is the reason why titillation, disaster, violence, crime, negativity and tragedy occupy the centre-stage in the content of the media. The chief criticism against this regress is mediocrity and homogeneity of the news content.

Indian journalism purchased by industrial houses

As in many areas of the world, Indian journalism is increasingly purchased by the entertainment business, e-commerce and industrial and business establishments, and of late by political and denominational interests. After all in India, politics, caste and parochial pandering return the highest economic profits and with none or marginal economic or intellectual investment and beyond the fear of audit.

I will now briefly survey contours of the essential elements of journalism.

Truth and Verification:

That journalism’s first obligation is to the truth is agreed. There is however utter confusion on what truth means. When a committee of certain journalists and the PEW Research Center for the People and the Press in 1999 conducted a survey and interviewed a large number of journalists in the West, all the interviewed members of the profession answered that truth means: getting the facts right. All members of the media, the electronic included, volunteered that truth is a primary mission.

Since news is the material that people use to learn and think about the world beyond themselves, the most important quality is that it should be usable and reliable. Truthfulness creates the sense of security that grows from awareness and is the essence of news.

The earliest colonial journalism was a heady mix of essay and fact; opinion and reality. Journalists trafficked in facts mixed with rumour. As it disentangled itself from political control in the 19th century, journalism in the West sought its first mass audience by relying on sensational crime, scandal, thrill seeking and celebrity worship – the age of yellow journalism had dawned; but even here the Lords of the Yellow Press sought to assure their readers that they could believe what they read even if the pledge was usually dishonoured.

Truth being subjective and relative; and journalism by nature being reactive and practical rather than philosophical and interpretive, journalism’s perception of truth may be different from truth as perceived by philosophers, by the legal community or by epistemologists.

Journalist Jack Fuller in his book, News Values: Ideas for an information age3 explains that there are two tests of truth according to philosophers. One is correspondence and the other is coherence. For journalism, these roughly translate into getting the facts straight and making sense of the facts. Coherence must be ultimate test of journalistic truth, Fuller concludes. Fuller observes: Regardless of what the radical sceptics argue, people still passionately believe in meaning. They want the whole picture, not just part of it…. They are tired of polarised discussion.

While context and coherence are the bedrock of the journalists’ version of truth, accuracy is as important. It is the foundation upon which everything else is built. If the foundation is faulty, everything is flawed. One of the risks of the new proliferation of news outlets, talk-shows and interpretative reporting is that it has left verification behind. A debate, for instance between political opponents at election time, arguing with false figures, on flawed data or purely on prejudice fails to inform. It only inflames and this takes a society nowhere.

To put it very briefly it is realistic to understand journalistic truth as a process; a continuing journey towards understanding, which begins with naked facts of an event or a transaction and builds over time with corresponding, developing, integrating and coherent fact presentation that give the reader/viewer a vision of the complex mosaic of truth. Truth in journalism is thus a calendar of facts getting fuller over time. Truth, like knowledge, comprises the progressive elimination of fiction, of ignorance.

Media needs to concentrate on synthesis and verification. Sift out the rumour, innuendo, the insignificant, and the spin and concentrate on what is truth and important about a story. Verification and synthesis become the backbone of the new gatekeeper role of the journalist, i.e., the role of being a news-maker.

Walter Lippmann wrote in 1922: The function of truth is to bring to light the hidden facts, to set them into relation with each other, and make a picture of reality upon which men can act. Since social transaction reality has a spatial element, the search for truth becomes a conversation continuing over time.

Who do journalists work for?

The next element is to realise who journalists work for, or rather should be working for. We understand that in today’s corporatized media, news organisations answer to many constituencies apart from primarily the corporate self-interest – to community institutions, local interest groups, parent companies, shareholders, advertisers and many more and other interests. All must be considered and served by a successful news organisation. Journalists inside such organisations and the organisations themselves as well must however have one allegiance above any other. Journalism’s first loyalty is to citizens. This is the implied covenant with the people.

People who gather news are not like employees of other companies. They have a social obligation that can and should actually override their employer’s immediate interests at times, and yet this obligation is a source of their employers’ success. Only in the latter part of 19th century did newspaper publishers begin to substitute editorial independence for political ideology. There are numerous shades of principles that inform the content of journalism’s first loyalty to citizens. It is a hugely complex process and outside the scope of a general paper like this.

Suffice it to note that rather than selling customers content, news people ought to be building a relationship with their audience, based on their values, on their judgment, authority, courage, professionalism, and commitment to community. Providing this creates a bond with the public, which the news organisations then rent to the advertisers. The business relationship of journalism is different from traditional consumer marketing, and in some ways more complex. It is a triangle. The audience is not the customer buying goods and services. The advertiser is. Yet the customer/advertiser has to be subordinate in that triangle to the third figure, the citizen.

In the corporatized media context, the public must understand their stake in the value of this freedom and demand that their democratic interests must be recognised not only by journalists but by the corporate leadership to whom the journalists now answer. If this does not occur, journalism independent of the corporate self-interest will disappear.

Independence from those they cover

Another element of journalism is independence from those they cover. This element applies even when journalism operates in the realm of opinion, criticism and commentary. The practitioners of journalism must therefore be independent and to a large extent neutral to class or economic status; race, caste, ethnicity, region and gender; as well as to the richness of conflict that exists in complex and large societies. This is so, since the identification of workable solutions that will achieve equilibrium in complex societies is the function of social debate and discourse and the compromises that societies make must emerge out ofthe crucible of such discussion and discourse. As the monitor of power however journalism must strive to put before the public all shades of opinions that abound in civil society.

Independent monitors of power

Journalists must serve as independent monitors of power. In one of American democracy’s founder James Madison’s words: Journalism is a bulwark of liberty, just as truth is the ultimate defence of the Press. In New York Times Co. vs. United States4, Justice Hugo Black emphasised the watchdog role of the press, he wrote: The press was protected so that it could bare the secrets of government and inform the people. Only a free and unrestrained press can effectively expose deception in government.

Being an independent monitor of power means simply and properly; watching over the powerful few in society on behalf of the many, to guard against tyranny. Professional investigative reporting must be distinguished however with muck-raking.

There are broadly three types of investigative reporting. Original investigative reporting which involves reporters themselves uncovering and documenting activities previously unknown to the public. This kind of investigative reporting often results in official public investigations about the subject or activity exposed; a case of the press pushing public institutions on behalf of the public. The uncovering and investigations into the recent CWG and Spectrum scams are illustrations of the beneficial role of this watchdog role of media.

The second type is interpretive investigative reporting. In this, reporting develops as the result of careful thought and analysis of an idea as well as dogged pursuit of facts to bring together information in a new, more complete context which provides deeper public understanding. This is possible only by a synthesis between facts and interpretation. Government programmes like SEZ allocations, industrial licensing, contracts and huge land grants can be effectively monitored for regularity only by exposing the connectivities between executive discretion and executive rain-making. This is an area that is not adequately or widely pursued in India.

Reporting on investigations is the third investigative category where reporting develops from the discovery or leak of information from an official investigation already under way or in preparation by others, usually government agencies. Reporting on investigations requires enormous due diligence.

Each type and methodology of reporting carries distinct skills, levels of commitment, professionalism, integrity, scepticism and risk. Too often reporters are not mindful of the distinctions and their own distinct role and the ethics involved.

Journalism as a public forum

Journalism must provide a forum for public criticism and comment. It must alert the people to public issues in a way that encourages judgment. The natural curiosity factor means that by reporting details of events, disclosing wrongdoing, or outlining a developing trend, journalism sets people wondering. As the public begins to react to these disclosures, the society becomes filled with the public voice – on radio and TV, call-in programmes, talk-shows, personal opinions and response pages and shows. Those in power hear these voices and make it their business to understand the nature of the public opinion developing around the subject.

The public forum function of the media counteracts the exclusive access that modern governments provide to powerful interest groups, business and industrial houses that operate through exclusive networking, lobbyists or specialised opinion makers and political propaganda. Media must decipher the spin and lies of contrived or commercialised argument in society. This forum component must be available for all parts of the community, not just the affluent or the demographically attractive sections. Since society is built on compromise, the public forum must include the broad areas of agreement where most of the public resides and where solutions to society’s problems are found.

News must be comprehensive and proportional

This element recognises that journalism is the modern cartography of society. It creates a map for citizens to navigate. Sensation and titillation make for good TRP ratings but are a poor guide for enriching social awareness or the democratic content. An hourly dose of scandal and titbits, say on the sexual escapades of artistes or the romances of the silver screen do not enrich the people, improve their lives or index the sovereignty of the individual, a condition which is critical to democracy. The nightly newscasts we observe have shifted to less reported news of the work of civic institutions to more of entertainment and celebrity attraction. Icons of the entertainment field or celebrities elsewhere offer more sound-bites on complex social, political or economic issues they do not adequately understand or know about, than experts or experienced persons in the relevant fields. Another modern day phenomenon is of experts manufactured by media; and some of the experts are pocket-borough experts of every field of human knowledge and often attached to specific media houses. This is neither comprehensive nor proportional reporting. By this strategy journalism opiates democracy and renders it sterile.

ABC news correspondent Robert Krulwich observed in 2000:

We have reached the point where entertainment divisions are doing the news and news divisions are doing the entertainment. In the spring of 2000 ABC hired movie actor Leonardo DiCaprio to interview President Bill Clinton about the environment but quickly abandoned the project amid staff protests. Manifest chaos had started dominating the news divisions.

Kovach and Rosenstiel observe that news journalism has lost its way in a large part since it has lost meaning in people’s lives; not only its traditional audience but the next generation as well. Journalists have lost the confidence of the people by failing to make the news comprehensive and proportional. Closer home we have evidence of this insecurity in the media. Otherwise why would channels proclaim that your (X) channel is the first to bring to you: Al Qaida’s, the World Trade Centre Terrorist attack; the Japanese earthquake; and the tsunami! Self-acclaim in news is the earliest and clearest symptom of content poverty and normative degeneration. Today almost every media outlet proclaims that it; and it alone, has the highest viewership.

Responsibility to individual conscience

Every journalist – from the newsroom to the boardroom – must have a personal sense of ethics and responsibility – a moral compass; this is yet another element of journalism. Each has the responsibility to voice their personal conscience out loud and allow others around them to do so as well. In the end journalism is an act of character. Since there are no laws of journalism, no regulations, no licensing, and no formal self-policing, and since journalism by its nature can be exploitative, a heavy burden rests on the ethics and judgment of the individual journalist and the individual organisation where he or she works. This is a difficult challenge to any profession. But for journalism there is the added tension between the public service role of the journalist – the aspect of the work that justifies its intrusiveness – and the business function that finances the work. Those who inhabit news organisations must recognise a personal obligation to differ with or challenge editors, owners, advertisers, and even citizens and the established authority, if fairness and accuracy require that they do so.

I have provided but a brief glimpse of this great institution of democracy and the core values that must inform it. I am no journalist. The little information about the profession and its norms, values and purposes that I have learnt comes from observation as a consumer of news and from scattered reading. But this much I gather. A journalist is not born. He has to be trained like any professional and the training, as the trends and norms of the profession show, must be rigorous and include the fundamental ethics, the nature of the personal character required and the difficulties of practicing this craft with integrity and commitment. An untrained journalist is a greater menace to society than an irresponsible government. And we have ample evidence of both before us today.

A free press is rooted in independence. Only a press free of government censor could tell the truth. In the modern context, that freedom must be expanded to mean independence from other institutions and interests as well – political parties, advertisers, business and industrial houses and cultural, racial and religious insularities as well. A conglomeration of news business threatens the survival of the Press as an independent institution of journalism. Journalism becomes a subsidiary inside large corporations and conglomerates, more fundamentally interested and grounded in other purposes, inimical to the elemental purposes of journalism.

Dialectical dilemma facing the profession

In the corporatized context, the challenge of our age is can the public rely on this new subordinated media to monitor powerful interests in society? Can we rely on a few large companies to sponsor that monitoring, even when it is not in their corporate interests? The essential question is, can journalism sustain in the 21st century, the purpose that was forged in it the three-and-a-half centuries that came before? This is in my humble view the great and momentous challenge and the dialectic dilemma that is facing the profession of journalism today.

I am but a consumer of the product of journalism. I have no expertise or familiarity with the skills and intellectual components that inform operations of media craft. What I harbour however are deep concerns and it is these inadequately reasoned concerns that I have placed before this constellation of talent and expertise in the field of public governance and adjudication. Each of you is more and eminently qualified to deliberate on the problems of the society, if you recognise that there is a problem. Please consider in your wisdom if the time has come to reflect on and identify the core and elemental values of journalism, examine and audit whether the fourth estate of our democracy is today on track or has deviated from the elemental path and what needs to be done.

Like the other estates of democracy, the media too is critical to our society; and its health is too valuable to be relegated exclusively to members of that segment, to reflect on and identify the necessity for calling in prophylactic or curative measures as need be, for its sustenance and nurture.

White’s remarks on media accountability

Aidan White, the General Secretary – International Federation of Journalists, presented a crisp but scintillating paper on the theme, Media Accountability: Setting Standards for Journalism and Democracy to the Bali Democracy Forum Workshop on December 9th, 2009. Some of his observations are noteworthy. The Bali workshop was about exploring and developing one of the key ethics of journalism –Accountability. The other three key ethics were identified as truth-telling; independence; and responsibility to the people Media serves. White observed:

But making ourselves accountable, owning up to our mistakes and revealing our frailties to the outside world is not something journalists ever find easy. There is nothing that journalists like better than exposing the hypocrisy of politicians, the corruption that is rife in the world of business and the frailties of celebrity. …

But while journalists relish dishing out punishment to society’s sinners and big-shots, they are notoriously thin skinned when it comes to admitting their own mistakes. The failure of media to be open and accountable is rightly identified as a symptom of arrogance and complacency.

Media accountability to be effective must be about the defence of press freedom not defence of the press yet many of the existing self-regulating press councils in the world have their roots in campaigns to avoid governmental legislation against the press. That has often created the impression that these press councils are self serving.

Media accountability in whatever form it comes must balance the rights of the individual and the community and the rights of the press to free expression. It must be framed in the notion that both the freedom and the regulation are indispensable if we want news media to provide citizens with the service they need to be informed participants in democratic life.

Accountability should also be based upon the principle of self-rule. That is why many press councils and media commissions are set up by the media themselves. But to be credible and to build public confidence they must operate with a high degree of independence from media and provide a set of rules under which people featured in the news media can complain if something is inaccurate, intrusive or unfair. They must also be open to participation from the communities that media serve.

White also pertinently observed:

Commercial media are increasingly incapable of meeting democracy’s needs. But what are the alternatives? One of them is the growing success of the non-profit media, particularly public broadcasting. In the United States, for instance, as the giants of the private media have been laid low, National Public Radio, whose funding comes from foundation grants, corporate grants and sponsorships, and licensing fees, has seen its listenership double in the past ten years. Foundations and other non-governmental subsidies are increasingly playing a role.

However they are employed, and by whom, journalists hold several keys to the fate of their craft. Journalists tend to see their work as a vocation, but their faith in that calling has been badly shaken in recent years. Morale is low. It is hard to do good work when your work is under threat, when the social and professional conditions are scarred by neglect, corruption and interference. The resulting impact on quality of journalism is palpable.

Media and the Judiciary:

Interaction, interdependence and on occasion tensions amongst the four estates are natural phenomena. After all these are overlapping magisteria of democratic arrangements. Each of these institutions is critical to the well being and sustenance and together these comprise the checks and balances, on which the edifice of democracy is constructed by the artifice of social evolution. Like all designed contrivances, each of democratic institutions has epochs of scintillating performance and of malodorous decay; often in simultaneity. It is perhaps difficult to construct a continuum of judicial outlook on media access and coverage of proceedings and of events/transactions having a litigative potential. Several judges have examples to justify critique of media coverage as being superficial, sensational, inaccurate, unfair, misleading, irresponsible, biased, and detrimental to public interest and the like. Though these condemnations may be defensible at times, on occasion we may be projecting our own difficulties with public’s perception of the work in courts or our frustrations about the limits or waning of the democratic state.

There may however be no point in declaring judicial war on the media, in any country. Media are more adept at capturing the public imagination, and thus such a course would be an exercise in futility, in any event. Further, such a defensive posture would inevitably lead to further insularity, escalation of hostilities and eventually to a destructive vortex of outcomes. We, in the judiciary could perhaps make a beginning by admitting, on occasion, our own failures and limitations and openly. This could start an internal discourse and eventually usher in better relationship with media; a more collegial and peaceful atmosphere could then emerge, over time. Media trial is a different problematic however and has critical consequences for the vitality of law enforcement, often debilitates judicial neutrality in adjudication and occasionally compromises fair trial outcomes.

Trial by media:

The role of the media vis-a`-vis the judiciary, critical issues that arise from the inter-play of these two vital institutions of democracy need to be considered as well. Trial by media is a phenomenon which occurs when the trajectory of media concerns is: feed the public what it is interested in and not what is in the public interest. Trial by media describes the impact of media coverage on a person’s reputation, often on his/her personal liberty and on the administration of justice, by manufacturing a widespread perception of guilt, without investigatorial, prosecutorial discipline and without mediation of accepted societal rules, both substantive and procedural, governing determination of malfeasant conduct, liable to criminal culpability or other species of conduct/action forbidden by law.

Does media influence judges? Felix Frankfurter, J recorded an admonition on this aspect (in John D. Pennekamp vs. State of Florida – (1946) 328 U.S. 331). He observed: No Judge fit to be one is likely to be influenced consciously….. However, Judges are also human and we know better than did our forbears how powerful is the pull of the unconscious and how treacherous the rational process….. and since Judges, however stalwart, are human, the delicate task of administering justice ought not to be made unduly difficult by irresponsible print….. in a particular controversy pending before a court and awaiting judgment, human beings, however strong, should not be torn from their moorings of impartiality by the undertone of extraneous influence. In securing freedom of speech, the Constitution hardly meant to create the right to influence Judges and Jurors.

Lord Dilhorne,in [Attorney General vs. BBC, 1981 A.C. 303 (H.L)] held similar views and he observed: It is sometimes asserted that no Judge will be influenced in his Judgment by anything said by the media and consequently that the need to prevent publication of matter prejudicial to the hearing of a case only exists where the decision rests with laymen. This claim to judicial superiority over human frailty is one that I find some difficulty in accepting. Every holder of a Judicial Office does his utmost not to let his mind be affected by what he has seen or heard or read outside the Court and he will not knowingly let himself be influenced in any way by the media, nor in my view will any layman experienced in the discharge of Judicial duties. Nevertheless, it should, I think, be recognized that a man may not be able to put that which he has seen, heard or read entirely out of his mind and that he may be subconsciously affected by it.

The Supreme Court (In Re. P.C. Sen) cautioned that the danger of prejudicial comment in media that must be guarded against, is on account of the impression that such comments might have on the Judge’s mind or even on the minds of the witnesses for a litigant.

Recent decisions of the apex Court however tacitly negate any pejorative influence of media coverage on the judicial mind. The observations of the Court in Balakrishna Pillai vs. State of Kerala and Zee News vs. Navjot Sandhu (2000 and 2003) deny that Judges might be influenced by propaganda, adverse publicity or media interviews. These curial conclusions, subjective as these are, do not appear to be based on any critical, scientific study or examination of the phenomenon of sub-liminal influence of audio-visual sensory exposures on cognitive behaviour.

Deeper study warranted

Former U.S. Vice-President Al Gore critically examined the pejorative influence of audio-visual communication on cognitive behaviour and on the vitality of democratic processes as well, by copious references to recent advances in psycho-social and neuro-scientific research, in an illuminating work – The Assault on Reason. A deeper study and reflection of this area is certainly warranted. Media effect on the judicial mind and whether court outcomes are affected on that account is a complex issue which defies easy or uniform analyses. The impact also depends on the levels in the judicial hierarchy, on particular judges and individual capacity to absorb the coercive influence of slanted media coverage. I have not come across any systematic study in this area.

Since it is outside the scope of this brief paper to consider at greater depth and acuity, the several dimensions of pejorative influence media reportage has on the administration of justice, I will rest content by stating that media coverage of events having a litigative/prosecutorial potential does have an impact, the degree and intensity whereof needs deeper study and analyses. Rights to privacy, to a fair trial, to nurture of reputation, to have a lis adjudicated by a neutral arbiter are some of the valuable rights adversely affected by media trials. As the New Zealand Court observed (in Solicitor General vs. Wellingdon Newspapers Ltd, 1995 (1) NZLR. 45): In the event of conflict between the concept of freedom of speech and the requirements of a fair trial, all other things being equal, the latter should prevail….. In pre trial publicity situations, the loss of freedom involved is not absolute. It is merely a delay. The loss is immediacy, that is precious to any journalist, but is as nothing compared to the need for fair trial.

As the three formal estates of a democracy, the legislature, the executive and the judiciary are essential to the preservation, sustenance and nurture of democracy, so too is the fourth estate – the media. Its independence, professionalism and ethical conduct are equally vital fundaments to a democratic way of life. When critical components of a complex system natural or designed go awry, the system is also in peril. Media is no exception to this norm. Eternal vigilance regarding the health of the media in a democracy is thus the price of liberty.

Justice Raghuram Goda.

Director,

National Judicial Academy India.

Endnotes:

1Declaration of the Vatican’s Holy Year Day for Journalists Address, 04-06-2000.

2 London: MacMillan, 1997

3 Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1996.

4 403 US 697 (1971).

(Paper presented at a session on “Media and Democracy” to a High Court Justices’ conference in 2017; the paper is partly drawn from a lecture by the author at an annual day function at a school of journalism in Andhra Pradesh, in 2007.)

Also Read: TV media’s celebrity trials: Freedom of Speech destroying Right to Fair Trial